How Does the Leading Gender Role in a Family Affect the Turnout of Children

In This Section

Introduction

The Political Participation Composite Score

Trends in Women's Political Participation

Voter Registration and Turnout

- The Affect of Voter Identification Laws on Women

The Women in Elected Role Index

- Trends in Women's Share of Elected Officials

- How the States Compare: Women in Elected Part

- Women in the U.Southward. Congress

- Women in State Legislatures

- Women in Statewide Elected Executive Role

- Women of Color in Elected Office

- Barriers to Political Office for Women

- Campaigning-While-Female

Women's Institutional Resources

Labor Unions and Women's Leadership

Appendix Tables

Introduction

The equal participation of women in politics and government is integral to building stiff communities and a vibrant democracy in which women and men tin thrive. Past voting, running for office, and engaging in civil order every bit leaders and activists, women shape laws, policies, and decision-making in ways that reverberate their interests and needs, equally well equally those of their families and communities.

Public stance polling shows that women limited unlike political preferences from men, even in the context of the recent recession and recovery, when the economy and jobs topped the listing of priorities for both women and men. A poll conducted past the Pew Enquiry Center (2012) found that women express business nigh issues such as education, wellness care, nativity control, abortion, the environment, and Medicare at higher rates than men. Women's engagement in the political process—both voting and running for function—is essential to ensuring that these issues are addressed in ways that reverberate their needs. Research indicates that women in elected function make the concerns of women, children, and families integral to their policy agendas (Heart for American Women and Politics n.d.; Swers 2002 and 2013).

Today, women found a powerful forcefulness in the electorate and inform policymaking at all levels of regime. Yet, women go along to be underrepresented in governments across the nation and face barriers that oftentimes brand information technology hard for them to exercise political ability and presume leadership positions in the public sphere. This affiliate presents data on several aspects of women's involvement in the political process in the The states: voter registration and turnout, female state and federal elected and appointed representation, and state-based institutional resources for women. It examines how women fare on these indicators of women's status, the progress women have made and where it has stalled, and how racial and indigenous disparities chemical compound gender disparities in specific forms of political participation.

| Best and Worst States on Women's Political Participation | |||||

State | Rank | Grade | State | Rank | Grade |

New Hampshire | one | B+ | Utah | 50 | F |

Minnesota | 2 | B | Texas | 49 | F |

Maine | iii | B | West Virginia | 48 | F |

Washington | 4 | B | Arkansas | 47 | F |

Massachusetts | five | B- | Louisiana | 46 | D- |

The Political Participation Composite Score

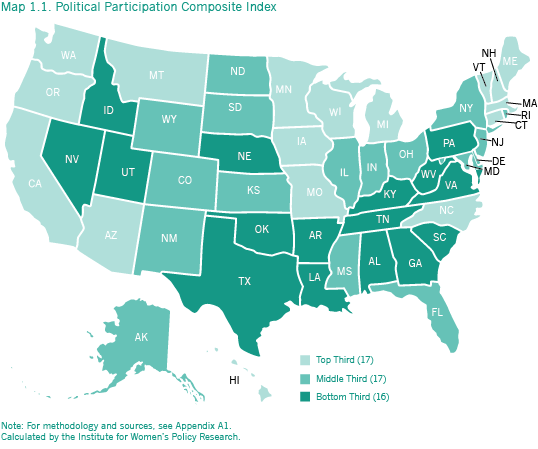

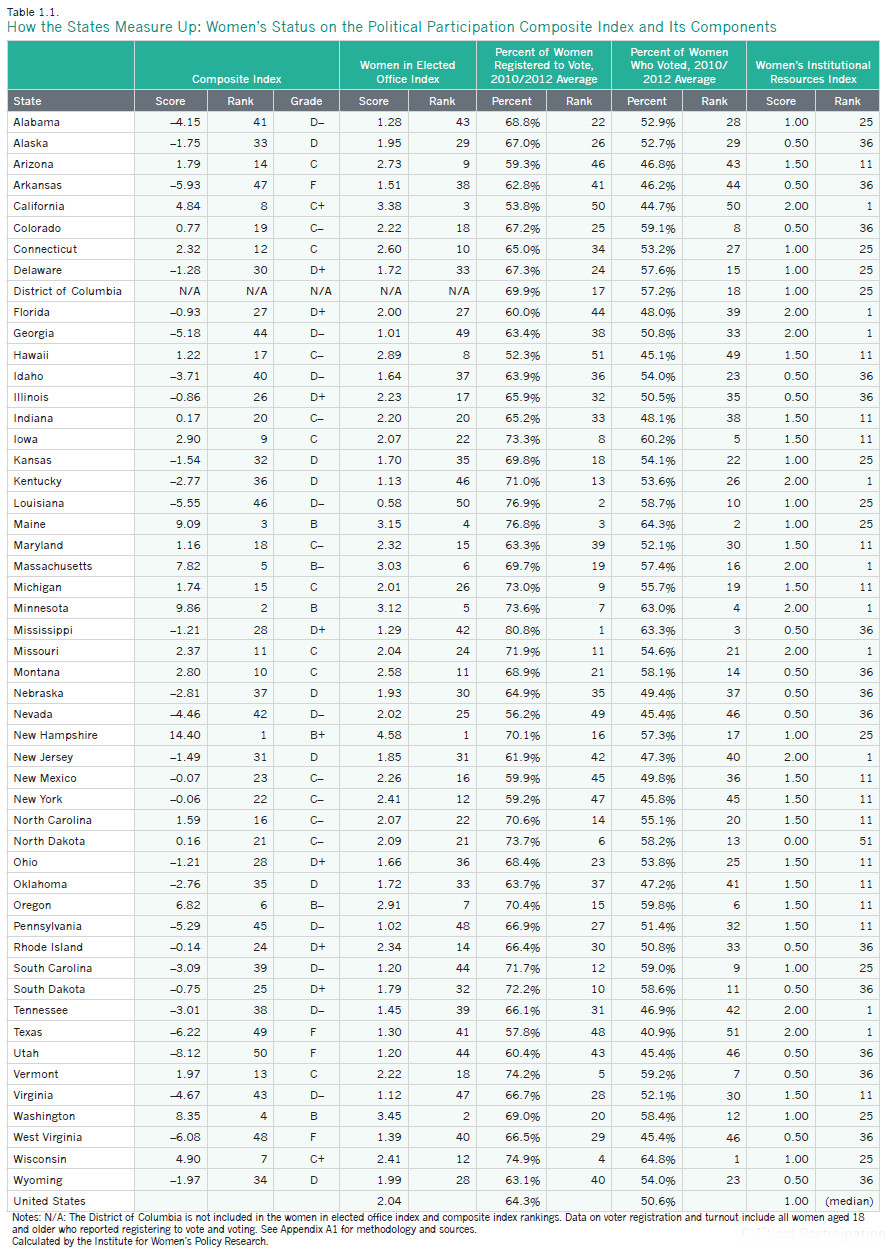

The Political Participation Composite Index combines four component indicators of women'due south political status: voter registration, voter turnout, representation in elected office, and women'southward institutional resources. Across the 50 states, composite scores range from a high of xiv.forty to a low of -8.12 (Table one.1), with the higher scores reflecting a stronger performance in this area of women's status and receiving higher letter grades.

- New Hampshire has the highest score for women's overall levels of political participation (Tabular array 1.1). Information technology ranks in the top ane-third for women's voter registration and voter turnout and is first in the nation for women in elected office, with a score that is approximately one-third college than that of the second-ranking state, Washington.1

- Utah has the lowest levels of women's political participation. The land ranks in the bottom ten for women's voter registration, women'south voter turnout, and women in elected function, and is 36th for the number of institutional resources in the land.

- Women'south political participation is highest overall in New England (with New Hampshire, Maine, and Massachusetts all in the top ten states), the Midwest (with Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Iowa ranking in the top ten), and the Pacific West (with California, Oregon, and Washington also amongst the ten best ranking states). Montana also ranks in the best ten.

- Women's political participation is everyman overall in the Due south (see Map 1.1). Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, Texas, Virginia, and Westward Virginia all rank in the bottom ten. Nevada and Pennsylvania are also a part of this group, along with the worst-ranking land, Utah.

- The highest class on the Political Participation Composite Index is a B+ (Table 1.1), which was given to one land, New Hampshire. This grade reflects the state'due south comparatively high levels of women'south political participation, but it also points to the need for comeback in this area of women's status. Arkansas, Texas, Utah, and West Virginia all received a grade of F. For information on how grades are determined, see Appendix A1.

Trends in Women's Political Participation

Betwixt 2004 and 2015, the number and share of women in state legislatures and in the U.S. Senate and Firm of Representatives increased, while the number and share of women in statewide elective executive office declined (CAWP 2015a; IWPR 2004). Women's voter registration and turnout also showed signs of both progress and lack of progress: the pct of women who registered to vote was lower in the 2010/2012 elections than in the 1998/2000 elections, merely the percentage of women who went to the polls increased during this period (Table 1.1; IWPR 2004).

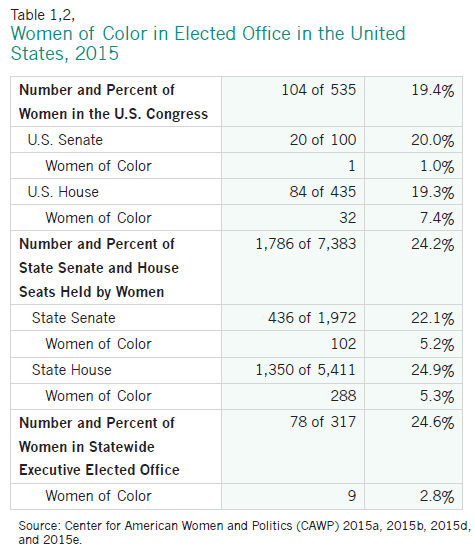

In 2015, twenty of 100 members of the U.S. Senate (20 per centum) and 84 of 435 members of the U.S. Business firm of Representatives (19.iii percent) are women. These numbers represent an increase since 2004, when women held 14 of 100 seats in the U.S. Senate and 60 of 435 seats in the U.S. House of Representatives (CAWP 2015a; IWPR 2004). Still, even though at an all-fourth dimension high for the U.S. Congress, the share of seats held by women in the U.S. Congress is well below women's share of the overall population.

- IWPR has calculated that at the rate of progress since 1960, women will not achieve 50 percent of seats in the U.Southward. Congress until 2117 (IWPR 2015a).

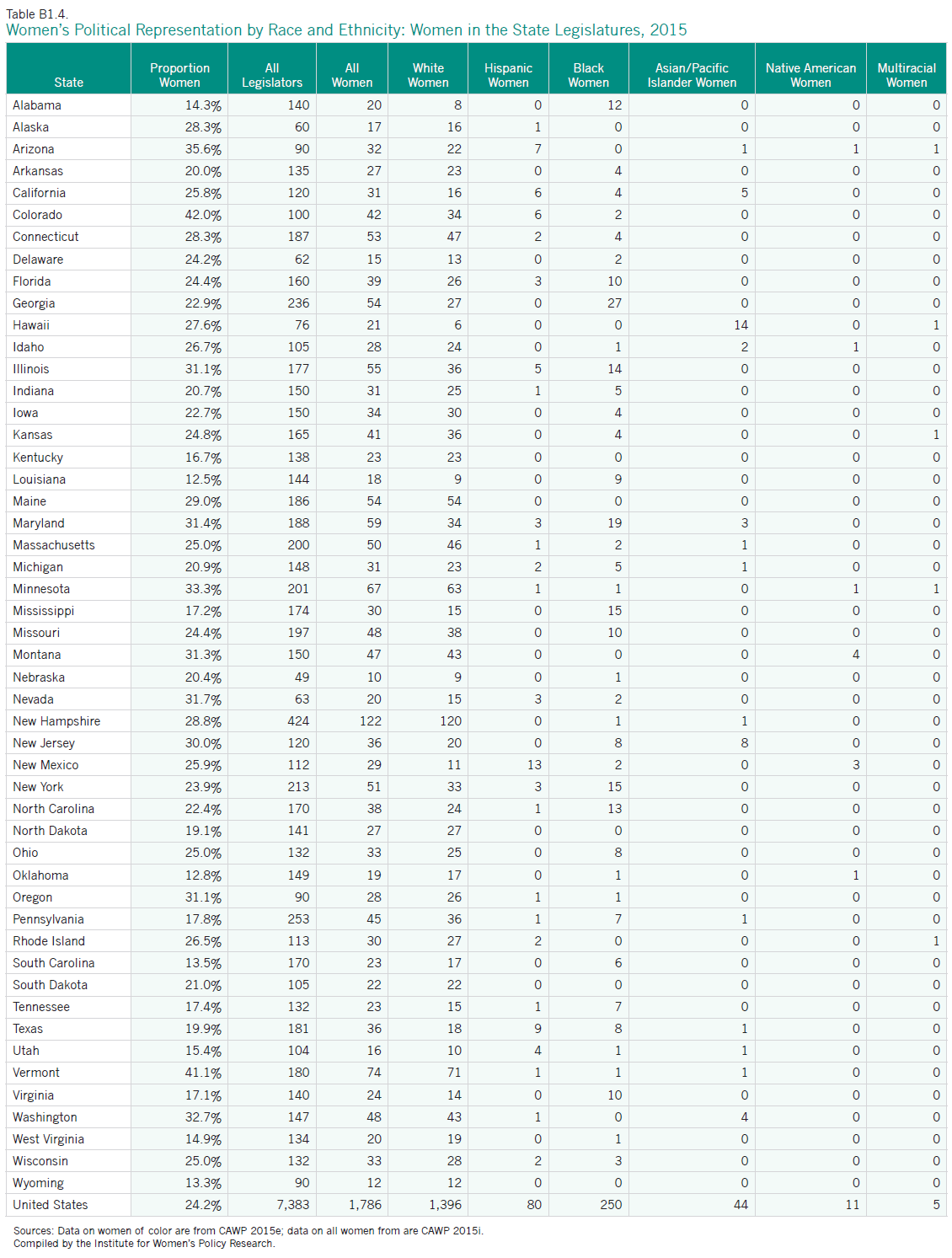

- Women held i,786 of 7,383 seats in state legislatures beyond the country in 2015 (24.2 percent), compared with 1,659 of vii,382 seats (22.5 percentage) in 2004 (CAWP 2015a; IWPR 2004).

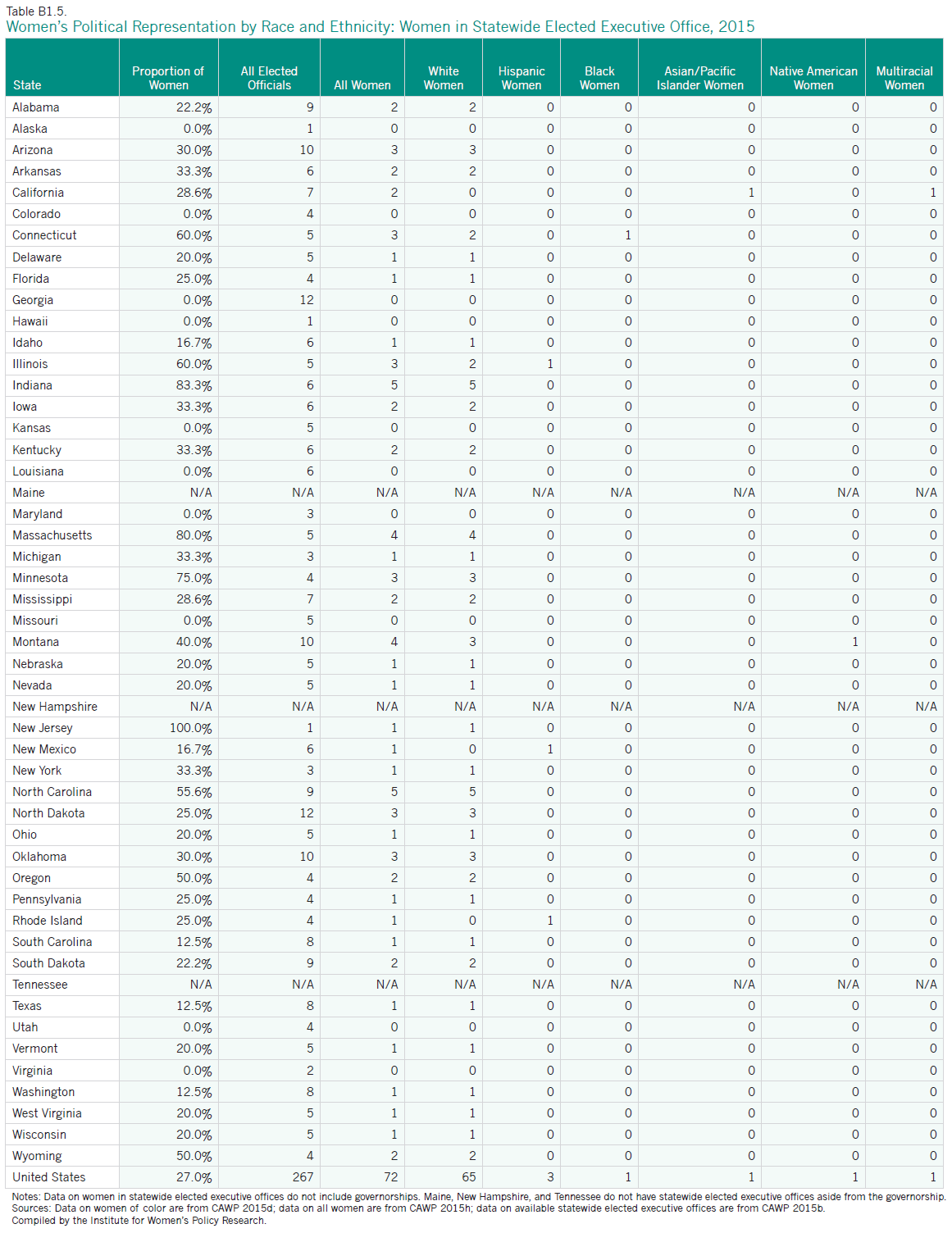

- The number of women in statewide constituent executive office declined from 81 (out of 315) in 2004 to 78 (out of 317) in 2015 (CAWP 2004a; CAWP 2015b).2

- In the 1998 and 2000 elections combined, 64.6 percent of women aged eighteen and older registered to vote and 49.3 percentage voted. In the 2010 and 2012 elections combined, 64.3 per centum of women registered to vote, and fifty.6 percent went to the polls (Tabular array i.1; IWPR 2004).

Voter Registration and Turnout

Voting is a critical way for women to express their concerns and ensure that their priorities are fully taken into account in public policy debates and decisions. By voting, women help to choose leaders who represent their interests and concerns. Although women in the United States were denied the right to vote until 1920 and in the following decades were often non considered serious political actors (Carroll and Zerrili 1993), women today take a meaning voice in deciding the outcomes of U.Southward. political elections. In the nation as a whole, women make up a majority of registered voters and have voted since 1980 at college rates in presidential elections than men (Center for American Women and Politics 2015c).

Women's stronger voter turnout relative to men's in the United States reflects an ongoing worldwide struggle to increment women'due south political participation. National-level efforts to expand opportunities for women to engage in political processes, and the international movement for women's rights, have helped to make the inclusion of women in the electorate acceptable in countries around the world. Although women'southward political participation varies among nations, women today vote in all countries with legislatures except Saudi Arabia, sometimes at college rates than men (Paxton, Kunovich, and Hughes 2007).

In the Usa, women are considerably more likely to be registered to vote and to go to the polls than men. Nationally, 61.five percent of women were registered to vote in the 2010 midterm election and 42.7 percent voted, compared with 57.9 percent of men who registered to vote and twoscore.9 percent who cast a election (U.Due south. Section of Commerce 2011). In the 2012 general ballot, 67.0 pct of women were registered to vote and 58.5 percent voted, compared with 63.1 percentage and 54.4 percent of men (U.Southward. Department of Commerce 2013). Registration and turnout are higher for both women and men in presidential election years than in midterm ballot years, when, in terms of national office, only members of Congress are elected.

Women'due south voting rates vary across the largest racial and ethnic groups. In 2012, blackness and non-Hispanic white women had the highest voting rates amidst the total female population aged 18 and older, at 66.1 percent and 64.5 percent, respectively (U.South. Department of Commerce 2013). Their voting rates were approximately twice as loftier as the rates for Hispanic women (33.9 percentage) and Asian women (32.0 percent; published rates from the U.S. Census Bureau are not available for Native American women).3 The higher voting rate amidst black women compared with non-Hispanic white women reflects a shift that first occurred in the 2008 elections, differing from the voting patterns of the elections up to 2004, when a larger share of white women had voted compared with whatsoever other group of women (U.South. Department of Commerce N.d.). Thursday is modify likely stems from the participation of the nation's first African American candidate in the presidential election (Philpot, Shaw, and McGowen 2009).

Nationwide, voting rates besides vary considerably among women of different ages. Immature women have a much lower voting rate than older women. In the 2012 election, 41.iii percent of women aged 18–24 voted, compared with 58.5 percent of adult women overall. Women aged 65–74 had the highest voting rate in 2012 at seventy.one percent, followed by women aged 75 years and older (65.half-dozen percent), women aged 45–64 years (65.0 percentage), and women aged 25–44 years (52.6 percent;

U.S. Department of Commerce 2013). Overall, 81.7 meg women reported having registered to vote in 2012 and 71.4 meg voted, compared with approximately 71.five one thousand thousand men who said they had registered to vote and 61.vi million who cast a ballot (U.S. Department of Commerce 2013).

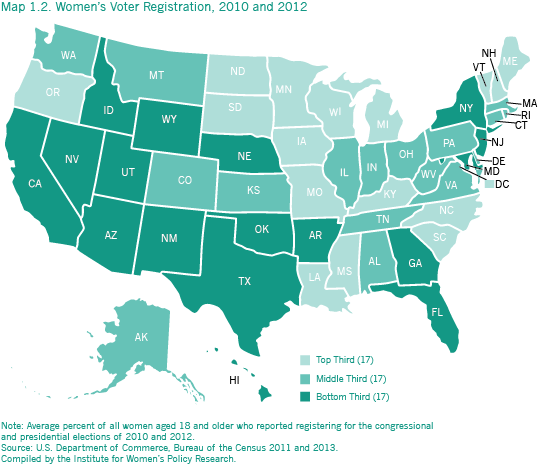

Women's voter registration rates vary beyond states (Map ane.2).

- Mississippi and Louisiana had the highest voter registration rates for women in 2010 and 2012 combined at 80.viii per centum and 76.9 percent, respectively. Half-dozen states in the Midwest—Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wisconsin—and two states in the Northeast (Maine and Vermont) were also in the height ten (Table 1.2).4

- Women'south voter registration is lowest overall in the western function of the U.s.a.. Hawaii had the lowest reported women's voter registration rate in 2010/2012 at 52.3 per centum, followed past California (53.8 percentage) and Nevada (56.2 percentage). Texas, Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah also rank in the bottom ten. They are joined by 2 Mid-Atlantic states—New Bailiwick of jersey and New York—and one Southern land (Florida; Table i.1).

- In 2010, women were more likely to be registered to vote than men in all merely three states: Alaska, Montana, and New Hampshire. Thursday due east state with the greatest gender gap in voter registration was Mississippi, where women'south voter registration exceeded men's past 9.5 percentage points (U.S. Section of Commerce 2011). In 2012, the same general pattern held true: a college per centum of women were registered to vote than men in all merely two states, Arizona and North Dakota. South Carolina had the largest gender gap in voter registration in this yr, with a rate for women that was viii.4 percent points college than the charge per unit for men (Table 1.1; U.S. Section of Commerce 2013).

- In 26 states, women's voter registration increased betwixt the 1998/2000 elections and the 2010/2012 elections, while in 24 states and the District of Columbia women'due south voter registration decreased. The states with the largest increases in women'south voter registration were Mississippi (6.0 percent points) and Arizona (5.1 percentage points). Us with the greatest decreases were N Dakota and Minnesota (17.4 and 7.four pct points, respectively; Tabular array 1.ane and IWPR 2004).

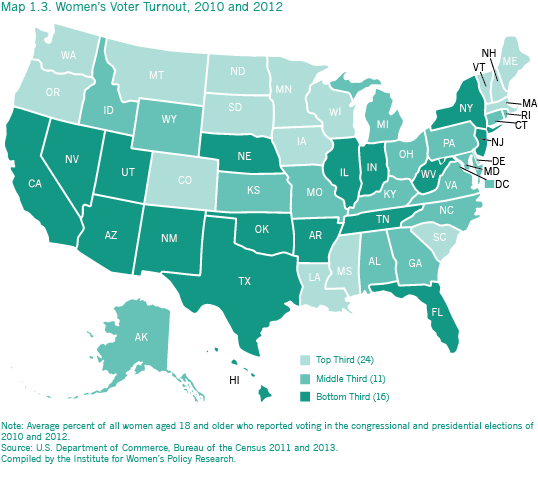

Women'southward voter turnout likewise varies among the states.

- Wisconsin had the highest women's voter turnout in the state in 2010/2012 at 64.8 percentage, followed past Maine (64.three pct) and Mississippi (63.3 percent). Other states that ranked in the top x were geographically diverse: Colorado, Iowa, Louisiana, Minnesota, Oregon, Due south Carolina, and Vermont (Table 1.ane; Map i.3).

- Women's voter turnout was everyman in Texas in 2010/2012, where just 40.9 percent of women reported voting. Voter turnout in Texas was substantially lower than in the 2d and third worst states, California (44.7 per centum) and Hawaii (45.1 percent). Other states that ranked amid the bottom ten for women's voter turnout include Arkansas, Arizona, Nevada, New York, Tennessee, Utah, and West Virginia (Tabular array 1.1).

- Women'south voter turnout was higher than men'southward in the District of Columbia and 39 states in 2010. Among jurisdictions where women'south voter turnout exceeded men's, the greatest differences were in Mississippi (7.6 points) and the District of Columbia (6.ane points). In 2012, women's voter turnout was higher than men'southward in all but ii states, Arizona and Northward Dakota (the aforementioned 2 states where women'southward voter registration was also lower than men's in this year). The largest differences in voter turnout rates were in S Carolina and Louisiana, where women'south turnout was higher than men'due south by 10.6 and 9.0 pct points, respectively (Table 1.ane; U.S. Department of Commerce 2011; U.S. Section of Commerce 2013).

- In 30 states, women'southward voter turnout increased betwixt the 1998/2000 elections and the 2010/2012 elections, while in twenty states and the District of Columbia their voter turnout decreased. The states with the largest increases in women'due south voter turnout were Mississippi (10.8 percentage points) and N Carolina (8.1 points). Us with the greatest decreases were Alaska (7.eight points) and Wyoming (6.3 points; Table i.1; IWPR 2004).

The Impact of Voter Identification Laws on Women

Although women constitute a powerful strength in the electorate, a new wave of recently passed state

voter identification laws has raised business that some women (and men) may be prevented from

casting ballots in time to come elections. The momentum behind voter identification laws in the United

States has increased since the passage of the first "strict" voter identification laws in Georgia and

Indiana in 2005, which required voters to show identification at the polling place at which they vote (other states had previously requested, but not required such identification, starting with S Carolina in 1950; National Conference of State Legislatures 2014a). As of March 2015, a total of 34 states had passed voter identification laws (National Conference of State Legislatures 2014b),

which varied across states in their requirements and degree of "strictness" (Keysar 2012). Some

states require that voters must show authorities-issued photo identification to vote, while others are more lenient and take non-photo identification such every bit a bank statement with proper name and accost (National Conference of State Legislatures 2014b).

Studies focusing on the populations most likely to exist affected by voter identification laws indicate

that women, especially low-income, older, minority, and married women, may exist specially affected by stringent voter identification laws (Brennan Center for Justice 2006; Gaskins and Iyer 2012; Sobel 2014). For example, women are more likely to be prevented from voting by laws that crave them to show multiple forms of identification with the aforementioned proper noun—such every bit a driver'southward license and birth certificate—since women who marry and divorce oft change their names. A national survey sponsored by the Brennan Center for Justice in 2006 found that more than one-half of women with access to a birth certificate did not have one that reflected their current name, and simply 66 per centum of women with access to whatever proof of citizenship had documents reflecting their electric current name (Brennan Middle for Justice 2006). The Brennan Center survey showed that xi percentage of the 987 randomly selected citizens of voting historic period did not have a photo ID. Low-income women (and men) who lack photograph identification may face up barriers like limited transportation and financial costs associated with accessing other identifying documents similar birth certificates and marriage licenses; once time, travel, and the costs of documents are factored in, the cost associated with a "free ID carte" can range from $75 to $175; when legal fees are included, the costs can exist every bit high as $1,500 (Sobel 2014). These laws could make acquiring an identification carte prohibitively expensive for women, who represent a greater share of those in poverty (IWPR 2015b). Older women may also exist affected by voter identification card requirements, since older populations are less likely to have a valid identification card than younger eligible voters (Brennan Center for Social Justice 2006).

The U.South. Authorities Accountability Office (GAO) conducted a quasi-experimental blueprint to meet if

voter ID laws affected turnout in Kansas and Tennessee past comparing the two states to neighboring states and controlling for certain factors. It found that "turnout amongst eligible and registered voters declined more in Kansas and Tennessee than it declined in comparing states—by an estimated 1.9 to 2.ii percentage points more in Kansas and two.two to iii.two percentage points more in Tennessee— and the results were consequent across the different data sources and voter populations used in the analysis." Information technology likewise found that young voters, those who had been registered for less than ane year, and African American voters had turnout reduced by larger amounts (U.Southward. GAO 2014).

Considering the laws are new and their impact is hard to measure, their furnishings are non yet fully

understood. Contempo studies accept yielded mixed results; some have found that voter identification

laws take a negative impact on voter turnout (Alvarez, Bailey, and Katz 2007; U.S. GAO 2014), while others take deemed the effects of such laws likewise minimal to make an impact (Mycoff, Wagner, and Wilson 2009). More than research is needed to determine exactly how laws that tighten identification rules for voting may affect women and men differentially.

The Women in Elected Part Alphabetize

Trends in Women's Share of Elected Officials

Although women have go increasingly agile in U.Due south. politics, the majority of political office holders at the state and federal levels are however male. Equally of March 2015, women held simply 104 of 535 (19.4 percent) seats in the U.S. Congress, ane,786 of 7,383 (24.2 percentage) seats in the nation's state legislatures, and 78 of 317 (24.six per centum) statewide elective executive offices (Table 1.ii). Amidst women of color, the level of representation is especially low: women of color—who constitute approximately xviii percent of the population aged 18 and older (IWPR 2015b)—concord most 6.2 percent of seats in the U.S. Congress, v.three percent of seats in land legislatures, and ii.8 percent of statewide constituent executive positions (Tabular array 1.ii).five

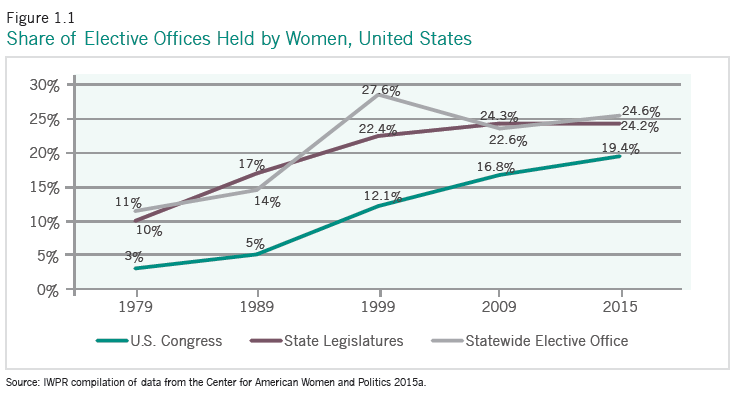

While these figures reflect substantial advances for women over the last several decades, little progress has been fabricated in recent years. In 1979, women held iii percent of seats in the U.Due south. Congress, x percent of state legislature seats, and 11 percent of statewide elective executive offices. The percentage of seats in the U.Southward. Congress held by women is now six times larger, and the percentage of state legislature and statewide elective executive offices held past women has more than doubled; yet, in the six year period between 2009 and 2015, women's representation in Congress grew only minimally, from 16.8 percent to xix.four pct. During this same time flow, their representation in statewide elective executive offices also barely inverse (increasing slightly from 22.6 pct to 24.half-dozen pct), and their representation in state legislatures decreased from 24.three percent to 24.ii per centum (Figure i.1).

Enquiry suggests that women generally win elected part at like rates as men (Dolan 2004), but fewer women run for function (Lawless and Fob 2008). Other studies emphasize the barriers women face nearly every footstep of the way (Baer and Hartmann 2014). Women are less likely than men to decide to run on their own and need to be recruited to run for office (Sanbonmatsu, Carroll, and Walsh 2009; Carroll and Sanbonmatsu 2013), however women are much less likely than men to be encouraged to run (Lawless and Play a joke on 2010) and to have access to networks of political leaders who could help them go elected (Goetz 2007). For some women, the lack of supportive policies for working families in the United States—such as subsidized child care and paid maternity and caregiving leaves—may exist a deterrent to running for elected office. 1 study that investigated how women brand the determination to run for elected office as well found that in some cases, women are discouraged by political party leaders, their peers, or other elected officeholders from running for or serving in college offices (Baer and Hartmann 2014).

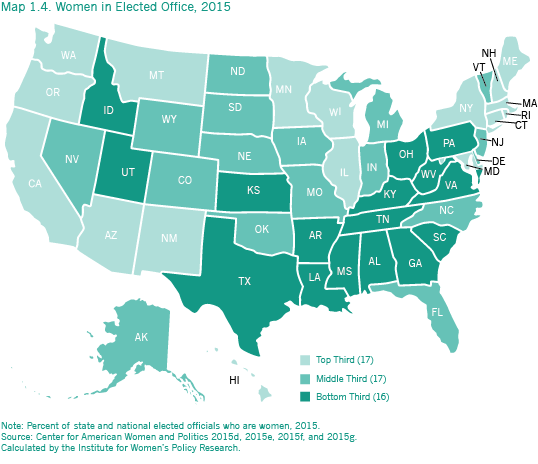

How united states of america Compare: Women in Elected Part

The Women in Elected Office index measures women'due south representation at state and national levels of government: the U.Southward. Congress, statewide elective offices, and state legislatures.

- New Hampshire has the highest score on the elected office index, followed past Washington and California (Table 1.ane).

- Louisiana has the everyman score on the index on women in elected office, followed past Georgia and Pennsylvania.

- The states with the highest scores are in New England and the W. In addition to New Hampshire, three New England states—Connecticut, Maine, and Massachusetts—rank in the tiptop ten. Ii western states in addition to California and Washington—Oregon and Hawaii—are also in the best-ranking group. Other states in the acme ten include Arizona and Minnesota.

- The states with the worst scores on women in elected part are primarily in the S. In improver to Louisiana and Georgia, six Southern states—Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi, S Carolina, Texas, and Virginia—are in the bottom ten. Pennsylvania and Utah as well rank in the lesser ten for women's representation in elected office.

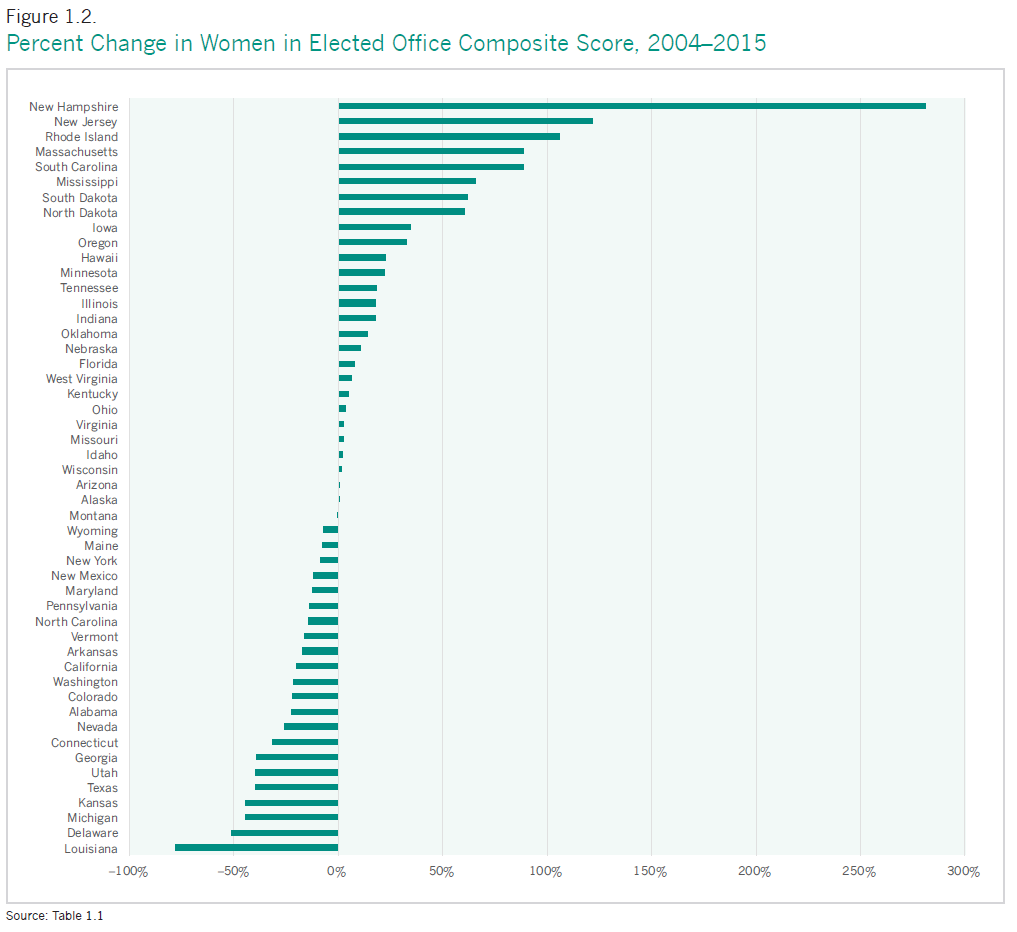

Effigy 1.2 demonstrates the pct change in states' scores in the women in elected part alphabetize between 2004 and 2015. 20-3 states declined in women's representation, while 27 states improved their score. Among the states that increased their score, New Hampshire (281.6 pct), New Jersey (121.three percent), and Rhode Island (106.0 per centum) all more than than doubled their score. Louisiana (-77.7 percent), Delaware (-fifty.eight percent), and Michigan (-44.iv pct) experienced the largest declines.

New Hampshire's substantial gains identify it first on the women in elected role index (upwardly from 42nd identify in 2004). Iii of its iv Congressional seats (both Senators and one of 2 representatives) are held by women. It ranks sixth for women in its country senate and is in the acme tertiary for women in its lower business firm. New Hampshire too has a woman governor.

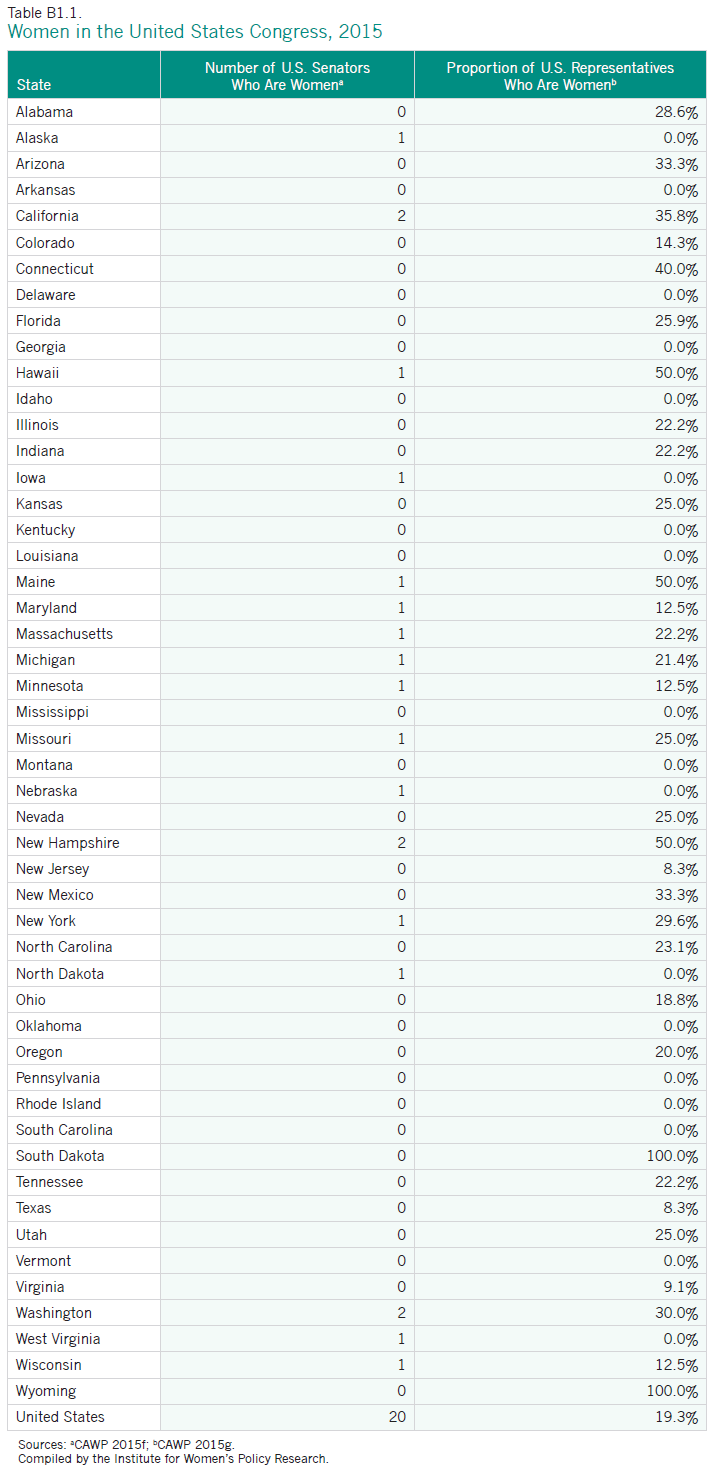

Women in the U.Due south. Congress

The xix.4 percentage of seats (104 of 535) that women hold in the U.Southward. Congress represents an all-time high (CAWP 2015a). Progress is moving at a snail's pace, however, and if it continues at the current charge per unit of alter since 1960, women will not achieve equal representation in Congress until 2117 (IWPR 2015a).

- In five states—Hawaii, Maine, New Hampshire, South Dakota, and Wyoming—women constitute at least one-half of the land's representatives to the U.S. House of Representatives. These are all small states: Hawaii, Maine, and New Hampshire each take two seats, and S Dakota and Wyoming each have ane seat. 18 states have no female representatives (come across Appendix B1.1).6

- There are only iii states in which both senators are female: California, New Hampshire, and Washington. Thirty-three states have no female senators (Appendix Table B1.1).

- Iii states accept never sent a adult female to either the U.Due south. House or the Senate: Delaware, Mississippi, and Vermont (CAWP 2015j).

- In 21 states, the share of representatives to the U.S. Congress who were female person increased betwixt 2004 and 2015, while in seven states the share decreased, and in 22 states the share stayed the aforementioned (Appendix Table B1.1; IWPR 2004).

- In x states, the share of Senators to the U.S. Congress who were female increased between 2004 and 2015, while in 5 states the share decreased, and in 35 states the share stayed the same (Appendix Table B1.1; IWPR 2004).

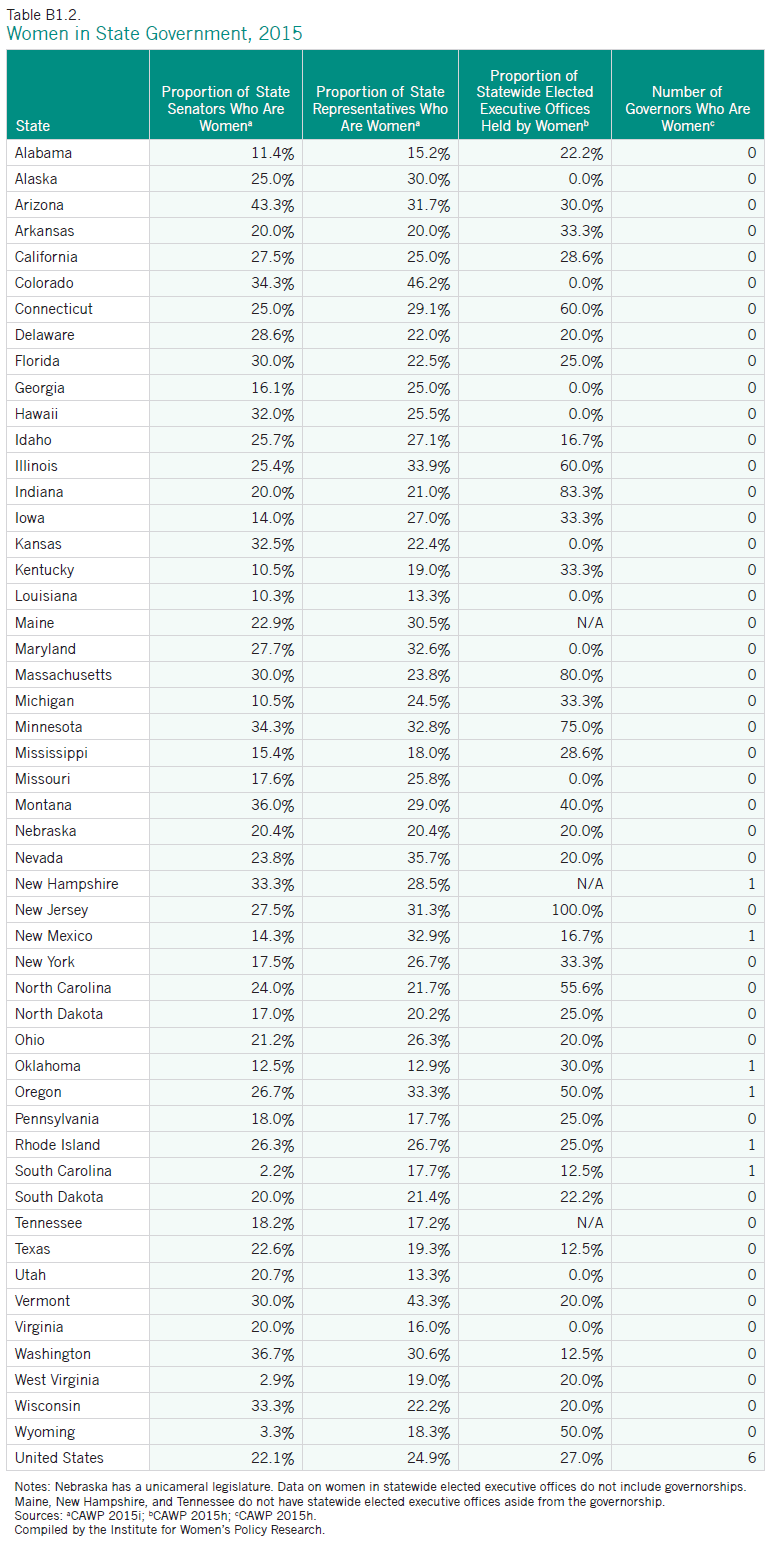

Women in Country Legislatures

Women's representation in state legislatures is progressing at unlike speeds in states across the nation. As of 2015, there were no states in which women held half of the seats in either the state senate or the state house or assembly.

- The share of land senate seats held by women is largest in Arizona (43.3 pct), Washington (36.7 pct), and Montana (36 pct) and smallest in Wyoming (3.3 percentage), West Virginia (2.9 percent), and S Carolina (two.2 percent; Appendix Tabular array B1.two).

- The share of seats in the country house or assembly held past women is largest in Colorado (46.2 percent) and Vermont (43.three percent), and smallest in Louisiana and Utah (13.3 percent each) and in Oklahoma (12.9 pct; Appendix Tabular array B1.two.)

- Between 2004 and 2015, the share of state senate seats held by women increased in 27 states, with the largest gains in Montana, where women'due south share of these seats increased from xvi.0 to 36.0 percent. Amongst the 16 states where women's share of seats decreased, Michigan experienced the greatest turn down (from 28.9 percent in 2004 to 10.five percent in 2015; Appendix Table B.two and CAWP 2004b).

- Between 2004 and 2015, the share of state house or assembly seats held by women increased in 32 states, with the largest gains in New Jersey, where women'south share of these seats grew from 16.3 percent to 31.iii pct. Amid the 17 states that experienced a decline, Utah had the largest subtract (from 22.7 percent to 13.3 percentage; Appendix Table B.2 and CAWP 2004b).

Women in Statewide Elected Executive Role

- As of March 2015, six states had female person governors: New Hampshire, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, and South Carolina. The largest number of female governors to accept served simultaneously is nine, in both 2004 and in 2007. Throughout U.South. history, 36 women take served as governors in 27 states (CAWP 2015k), out of a full of more than 2,300 governors (National Governors Association 2015).

- In nine states, women hold at least one-half of statewide elected executive office positions aside from governorships. 10 states have no women in their statewide elected executive offices vii (Appendix Table B1.2).

- Between 2004 and 2015, the share of women in statewide elected executive offices other than governorships increased in 17 states, decreased in 16 states, and stayed the same in fourteen states.8

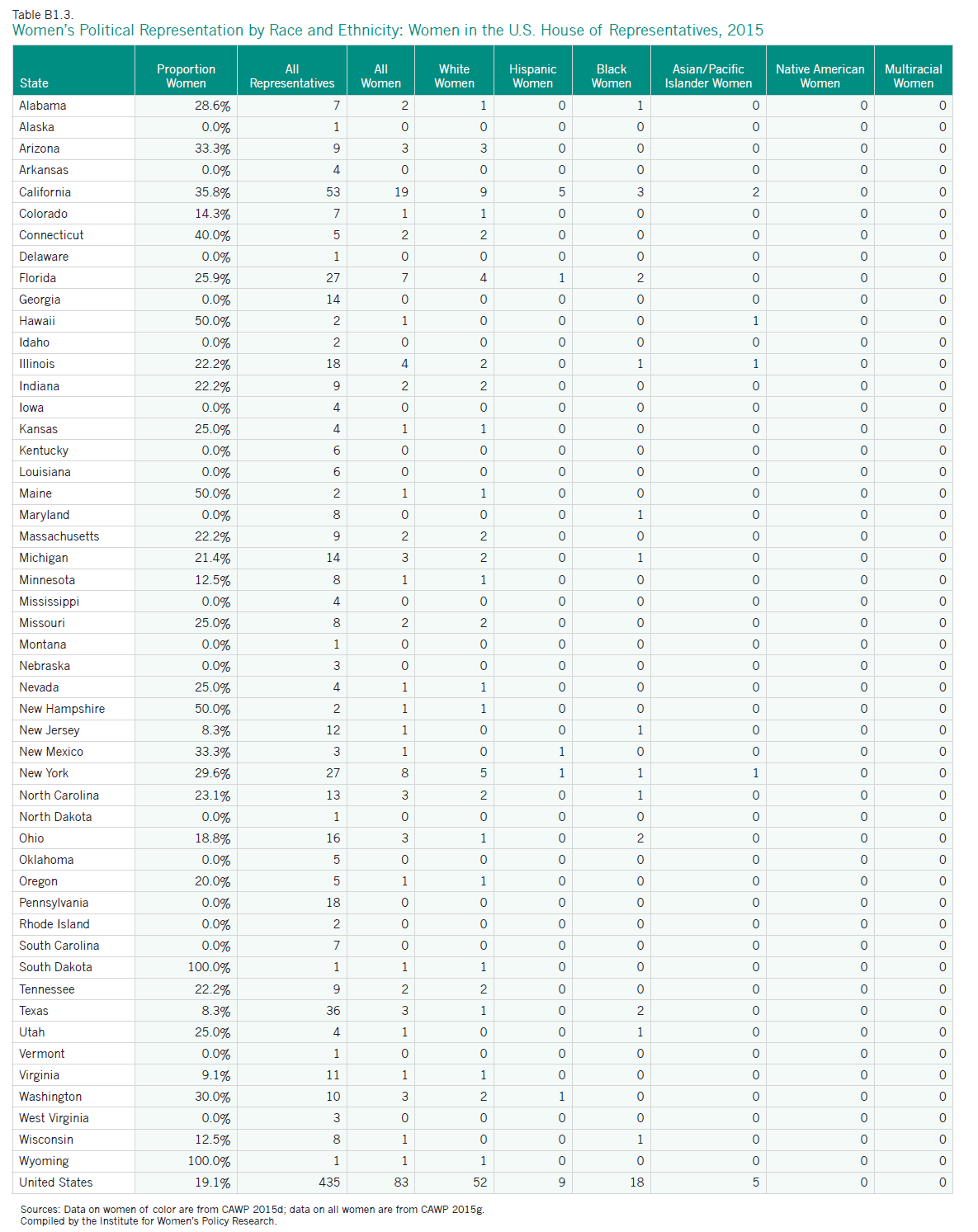

Women of Colour in Elected Office

While women of color accept made progress in gaining representation, they are still vastly underrepresented at every level of government reviewed hither.

- Women of color make upward 7.four percentage (32 of 435 representatives) of the U.S. House of Representatives (Appendix Table B1.3). California has the greatest number of women of colour in the House, at 10 of its 53 representatives. Florida and New York, each with 27 members, each have three women of colour serving in the Firm. The states with the greatest proportions of women of color in the Business firm are Hawaii (50.0 percent, or one of ii members), New Mexico (33.iii percentage, or ane of three members), and Utah (25.0 percent, or i of four members). Thirty-4 states take no women of color serving as representatives.

- Of the 32 women of color serving in the House of Representatives, xviii are blackness, nine are Hispanic, and five are Asian/Pacific Islander.

- At that place is simply one woman of color—Senator Mazie Hirono of Hawaii—serving in the U.S. Senate (CAWP 2015d).

- Women of color are 5.3 percentage (390 of vii,383 legislators) of the country legislators in the United States (Appendix Table B1.iv). The states with the greatest number of women of colour legislators are Maryland (25 of 188 legislators) and Georgia (27 of 236 legislators). The states with the greatest proportions of women of colour in state legislatures are Hawaii (15 of 76 legislators, or 19.7 percent), and New Mexico (18 of 112 legislators, or sixteen.ane percent). Five states— Kentucky, Maine, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming—have no women of color serving in their state legislatures.

- Of the 390 women of color state legislators, 250 are blackness, 80 are Hispanic, 44 are Asian/Pacific Islander, eleven are Native American, and 5 are multiracial.

- There are 9 women of color in statewide executive elective office, including ii governors (CAWP 2015d). California and New United mexican states take the greatest number of women of color in statewide elective office, at two each. Connecticut, Illinois, Montana, Rhode Island, and Due south Carolina each have one woman of colour serving in statewide elective role. Of the nine, iv are Hispanic, two are Asian/Pacific islander, one is African American, one is Native American, and one is multiracial.

- Two Governors—Nikki Haley of S Carolina, and Susana Martinez of New Mexico—are women of color (CAWP 2015d). Governor Haley is Indian American and Governor Martinez is Latina.

Barriers to Political Office for Women

Women'due south active participation in elective office is critical to ensuring the democratic character of our nation. Still, women are largely underrepresented at every level of office, and progress toward achieving parity has nearly stalled.

In a contempo report, Shifting Gears: How Women Navigate the Road to Higher Office (Hunt Alternatives Fund 2014), Political Parity, a program of the Hunt Alternatives Fund, has identified the barriers women face up in seeking political office, especially in attempting to move to college political office (such as governorships and positions in the U.Southward. Congress). The report uses the analogy of the "driver" and "the route" to describe the contend in the political science field about whether women are holding themselves back because they have less appetite (Lawless and Fox 2012) or whether women are held back by diverse pot holes and barriers along the road (Baer and Hartmann 2014; Carroll and Sanbonmatsu 2013). It suggests that both the driver and the road are essential to whatsoever journey. Women are frequently seen to perform as well as men when they campaign for office—with similar fund-raising totals and electoral success—yet fewer women decide to pursue candidacy.

One study on the "driver" side attributes the underrepresentation of women in higher office to a gender gap in political ambition (Lawless and Flim-flam 2012). The study analyzed data from a survey of four,000 male person and female potential candidates—those who are well situated to pursue candidacy—and establish that 62 per centum of men, compared with 46 percent of women had ever considered running for role, and 22 percent of men and xiv pct of women were interested in running for office in the future. On the "road" side, a qualitative written report of threescore women candidates who have run for the U.South. Congress or for state and local offices (or have seriously considered running for office) identified barriers women face to running for higher part, and action items for increasing the number of women in elected office. Amid the virtually cited barriers were fundraising, which must be ramped up to a much higher level when running for Congress or a state-wide office—making the enquire, developing relationships with donors and so that when asked, donors respond, and having access to good phone call lists—as well as campaigning while female person, balancing family obligations and role holding with campaigning, and the authority of informal, male person political networks that oftentimes exclude women (Baer and Hartmann 2014).

Proposed action items for increasing the number of female officeholders include recruiting and asking women to run; expanding and enhancing woman-centered campaign training, especially on-going training that emphasizes pursuing politics as a career and making longer run plans for strategically choosing which offices to seek; launching an organized effort to build the pipeline to office and improve strategic race placement; providing for mentoring and sponsorship of women candidates and elected officials; increasing agreement of fundraising, which includes building relationships with sponsors, who may be established office holders or those who practice not hold political role but often support candidates they think can be successful; strengthening networks of women'south organizations; raising sensation among the public of female role models and increasing respect for women; and making campaigning and office holding more family unit-friendly (Political Parity 2014). Many of these strategies require that outside groups, such as a strengthened network of women's organizations, become more active in supporting women who run for office (Baer and Hartmann 2014; Carroll and Sanbonmatsu 2013).

Following through with these recommendations may make the difference in encouraging more women to run for office and in helping them excel in one case they go there. Simply then will our institutions of government be able to fully drag women's perspectives and policy priorities and volition the nation be able to benefit from women's leadership.

Candidature-While-Female

"Campaigning-while-female" refers to experiences that many women running for elective office believe are different from men'south. Campaigning-while-female highlights experiences that differ from incidents of discrimination. Bigotry is seen in instances where women candidates and elected officials may receive fewer resources such as campaign donations and party fiscal support, or fewer opportunities to sponsor legislation or participate in influential committees (Baer and Hartmann 2014). Rather, campaigning-while-female refers to a range of inappropriate and sexist comments and behaviors, such as a focus on outward appearance, questioning of qualifications for office, and increased curiosity about a woman'due south personal life, such as her role as a married woman and female parent. While male person candidates may besides experience unwelcome curiosity well-nigh their private lives, women believe these concerns are expressed much more strongly to women candidates, including frequent comments, for single women, on their dating life (Baer and Hartmann 2014). Women candidates and elected officials take expressed the need to be always "on," to always detect societal norms for how a adult female in leadership should act and look. Many have experienced the "double bind" and seek to overcome it—they human activity similar stiff leaders but hope to escape the stigma of being labeled an aggressive woman (Political Parity 2014).

Campaigning-while-female is relatively common; one written report of women candidates and constituent officials plant that approximately 9 in 10 (88 percent) participants said women's campaign experiences are unlike from men'southward (Baer and Hartmann 2014). The about notorious instance of campaigning-while-female person came about during the 2008 presidential election, when Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton and Republican Vice Presidential nominee Sarah Palin were frequently portrayed every bit the "bitch" and the "ditz" (New York Magazine, 2008). This sexist treatment is almost commonly associated with media coverage, but women too receive it from constituents, donors, peers and colleagues, and political party operatives and leaders.

The sexist treatment of women candidates and elected officials may dissuade women from running for political office, or may influence a voter's likelihood of supporting a female candidate (Lake Enquiry Partners 2010). In one survey of 800 likely voters nationwide, both female and male person participants who heard sexist attacks by media on a hypothetical female candidate were less probable to vote for her than the command group that heard a not-sexist attack on the candidate. There was besides backlash against the male candidate for issuing sexist attacks; yet, the female person candidate endured the greatest toll on her favorability and the likelihood that a voter might vote for her. When the female person candidate or a surrogate called out the sexist treatment by the media, the support for the female candidate resurged (Lake Research Partners 2010). This finding emphasizes the importance of candidates and supportive networks calling out double standards and unfair treatment non only by the media only also by other candidates (Political Parity 2014).

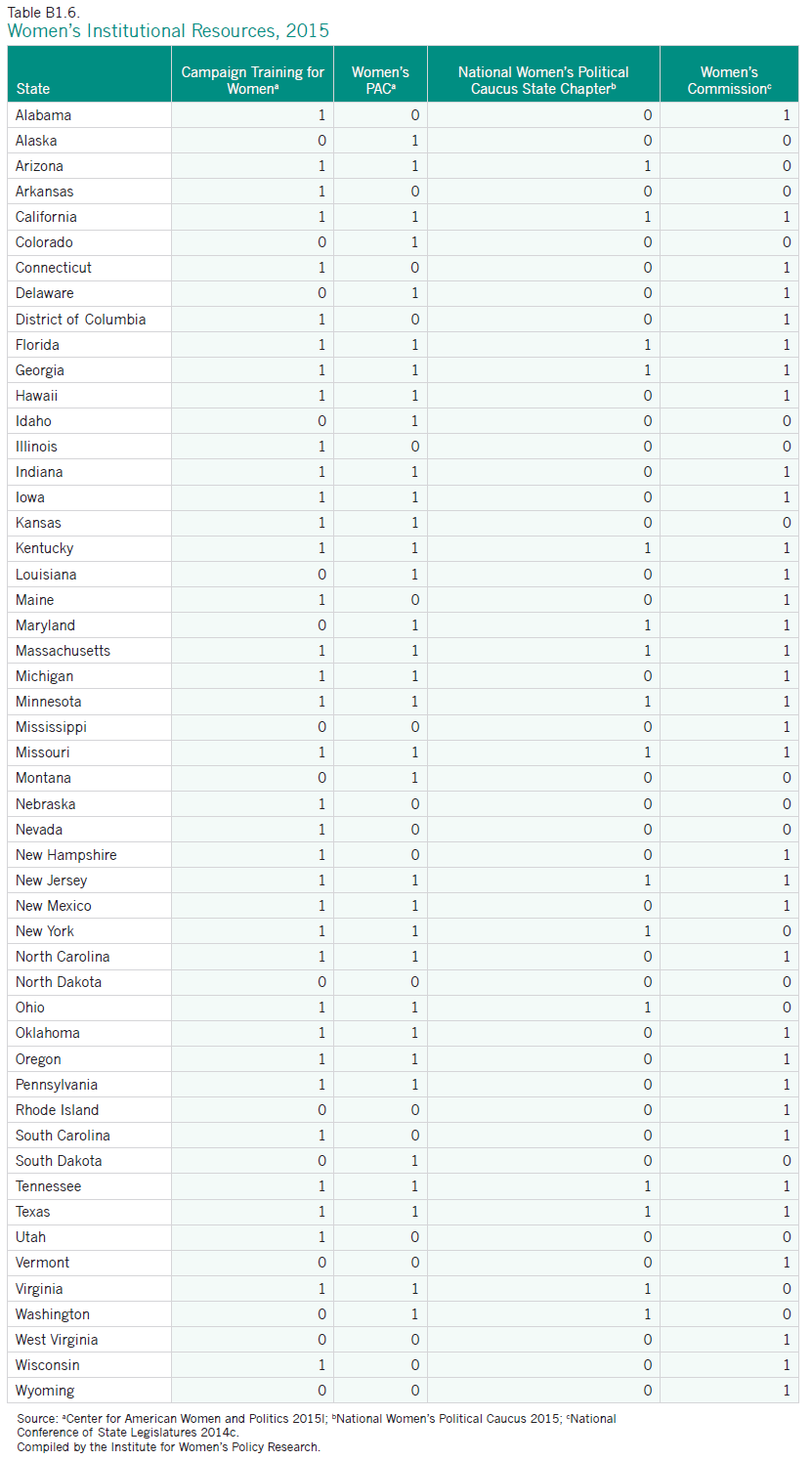

Women's Institutional Resources

In addition to women's voting and election to local, state, and federal offices, institutional resources dedicated to helping women succeed in the political loonshit and to promoting and prioritizing women's policy issues play a key role in connecting women constituents to policymakers. Such resources include entrada trainings for women, women's Political Action Committees (PACs), women's commissions, and state chapters of the National Women's Political Conclave (NWPC). These institutional resources serve to dilate the voices of women in government and increase the admission of women, their families, and their communities to decision makers on the policy issues that matter well-nigh to them. Institutional resource and statewide associations too provide peer support systems for female elected officials and constitute breezy networks that can aid them navigate a political system that remains predominantly male (Strimling 1986).

Campaign trainings for women provide valuable insight into running a successful campaign and strengthen the pipeline to higher office. I study constitute that nine in ten women who participated in a training before running found it extremely helpful; many also believed that campaign trainings should be expanded to be more women-axial so as to address the event of "candidature-while-female" (Baer and Hartmann 2014). Experienced women candidates too expressed a demand for a range of candidate training, from running for one'due south first office to running for a seat in one's congressional delegation, which as a national office requires the candidate to larn a new range of skills. Most preparation, however, seems to be aimed at encouraging women to run for their offset office.

Political action committees (PACs) enhance and spend money for the purpose of electing and defeating candidates. A PAC may give directly to a candidate committee, a national party committee, or another PAC, within the contribution limits (Open Secrets 2015). A women's PAC may be critical to supplying a female candidate with the entrada contributions she needs to launch a successful campaign. A women's PAC may also bolster candidates who support women-friendly policy and legislation. In 2014, there were 23 national and 47 state or local PACs or donor networks that either gave money primarily to women candidates or had a primarily female donor base (CAWP 2014).

A commission for women is typically established past legislation or executive club and works to prioritize issues that may disproportionately bear on women's lives (National Conference of State Legislatures 2014c). In many states across the nation, women's commissions—which tin operate at the city, county, or state level—strive to place inequities in laws, policies, and practices and recommend changes to accost them. Women's commissions may appoint in a diverseness of activities to benefit women in their geographic areas, including, but not limited to, conducting research on problems affecting the lives of women and families, holding briefings to educate the public and legislators on these issues, developing a legislative agenda, and advocating for gender balance in leadership throughout both the public and private sectors (Cecilia Zamora, National Association of Commissions for Women, personal communication, May 1, 2015).

The National Women'southward Political Caucus (NWPC) is a multi-partisan, grassroots organization dedicated to increasing the number of women who run for office and who are elected or appointed into leadership positions (National Women'southward Political Caucus 2015). The NWPC has state and local capacity that piece of work with women in their communities to provide institutional support by recruiting women to run for part, endorsing women candidates, helping them raise campaign contributions, and providing them with campaign trainings (National Women'south Political Caucus 2015).

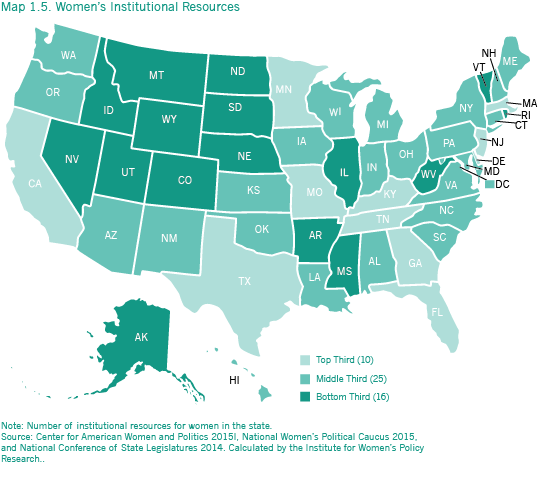

- Thirty-five states have state-level campaign trainings specifically for women, 34 states accept a women's commission, 33 states have a women'southward PAC, and 16 states have chapters of the National Women'southward Political Caucus (Appendix Table B1.6).

- X states have all four of these institutional resource for women at the land level: California, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Missouri, New Jersey, Tennessee, and Texas. These states are all tied for the kickoff place ranking and are shown as the tiptop third in Map 1.v. An additional 14 have three institutional resources and are all tied for 11th place. 10 states plus the Commune of Columbia take two. This group of 25 jurisdictions is shown as the middle third in Map 1.5. The lesser third consists of xv states that accept i institutional resources and the 1 state—North Dakota—that has no resources to help women in their political participation. North Dakota ranks 51st on this indicator of women'south status (Appendix Table B1.vi).

Labor Unions and Women'south Leadership

The labor movement spearheaded many of the bones workplace protections we enjoy today, such as the minimum wage, the 40-hr work week, overtime pay, and adequate workplace wellness and prophylactic. Unions play an important role in collective bargaining for workers' rights, and in raising issues to the forefront of the national calendar. On many policy issues, labor unions take taken the lead in both national and country policy evolution.

Women's participation in unions is benign for several reasons. Unionized women have greater earnings—$212, or 30.9 percent more per calendar week—and higher rates of health insurance coverage than nonunionized women (IWPR 2015c; IWPR 2015d). Women's leadership is as well critical to promoting problems of importance to women and families—including paycheck fairness, access to affordable child care, raising the minimum wage, and expanding access to paid ill days—and raising these problems to the forefront of unions' agendas.

Women make upwardly a large proportion of matrimony members and take been closing the gender gap in wedlock membership. In 2004, 57.four percentage of members were male person, while 42.6 percentage were female (U.S. Section of Labor 2005). Past 2014, women were 45.5 pct, or six.half-dozen million of fourteen.half dozen million wedlock members (U.S. Department of Labor 2015a). Of wage and bacon workers overall in the United States, 11.seven pct of men and ten.5 pct of women are members of unions, with public sector workers five time as likely to belong to a union as individual sector workers (35.7 percent compared with six.6 per centum; U.S. Department of Labor 2015b).

Women are also working toward amend representation within wedlock leadership. Women are xviii.ii per-cent (ten out of 55) of the Executive Quango of the AFL-CIO, 25.7 percent (9 of 35) of the International Vice Presidents of AFSCME, 38.one percent (8 of 21) of the Executive Board of the CWA, 42.9 percent (eighteen of 42) of the AFT Vice Presidents, fifty.0 percent (4 of viii) of the leadership of SEIU, and 60.0 percent (3 of 5) of the General Officers of UNITE (AFL-CIO 2015; AFSCME 2015; AFT 2015; CWA 2015; SEIU 2015; UNITE Here 2015). While these numbers do not provide information almost the leadership of the local capacity of these unions, they do speak to the limerick of their national marriage leaderships.

Several obstacles often make information technology difficult for women to get involved in union leadership. One qualitative written report of women union activists identified half dozen barriers that women face up in union piece of work: women experience difficulty making room for the time demands of union leadership, especially given their competing family obligations; women and people of colour take an acute fearfulness of retribution by employers; few women serve at the top of union leadership, where they could serve as office models to other women activists; women express discomfort with public authority based on an understanding that this is not a female role; women are non aware of how matrimony leadership may do good their lives as workers; and unions place inadequate accent on the priorities and concerns of women (Caiazza 2007). The written report also identified 7 strategies for promoting women's leadership within unions. Unions can highlight the importance of women's contributions; provide trainings on effective ways to mobilize women; encourage and back up more women in leadership positions both nationally and locally; create and strengthen mentoring programs for women; provide dedicated space for women to voice their concerns; address women's priorities by using imagery and language that reflects their experiences; and provide flexible options for involvement by finding artistic times and places to run across and providing supports such equally childcare (Caiazza 2007).

These strategies encourage women's activism and strengthen unions by enabling them to be more than inclusive of the needs and priorities of all their members.

Conclusion

Although there are many institutions that promote women'south civic date and political participation, obstacles to women's political participation and leadership persist. Women'due south lesser economic resources (as shown in other releases from the Status of Women in the States project) compared with men's, their greater caregiving responsibilities, their more limited access to important supports that would help them to run for office, and succeed as role holders, and the greater scrutiny that women candidates seem to face up from the public and the media all restrict women's political participation and leadership in states across the nation. Progress in advancing women'south political status continues to move at a glacial pace. Equally of 2015, women'south representation at all levels of government remains well beneath their share of the overall population. IWPR projects that women will not reach fifty percent of the U.South. Congress until 2117 (IWPR 2015a). Efforts to recruit more women to run for part and to increase their success equally candidates and role holders will exist crucial to increasing their representation in the coming years and decades.

Methodology

Appendix Tables

Source: https://statusofwomendata.org/explore-the-data/political-participation/political-participation-full-section/

0 Response to "How Does the Leading Gender Role in a Family Affect the Turnout of Children"

Post a Comment